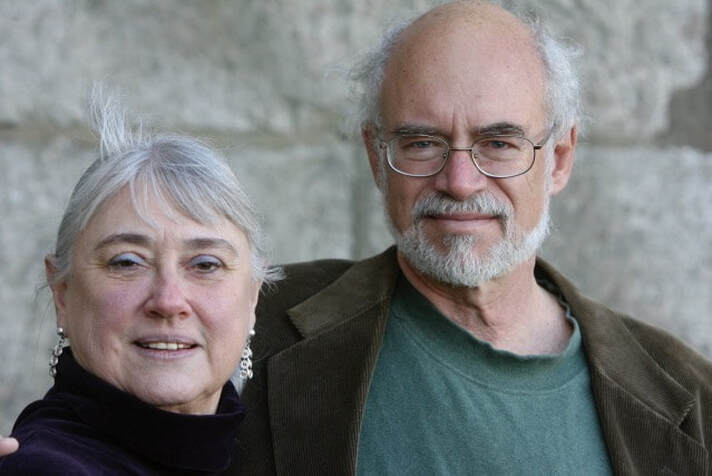

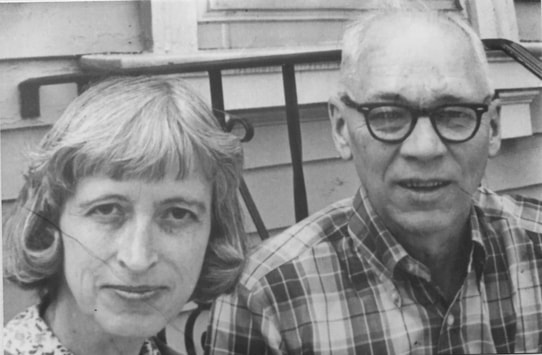

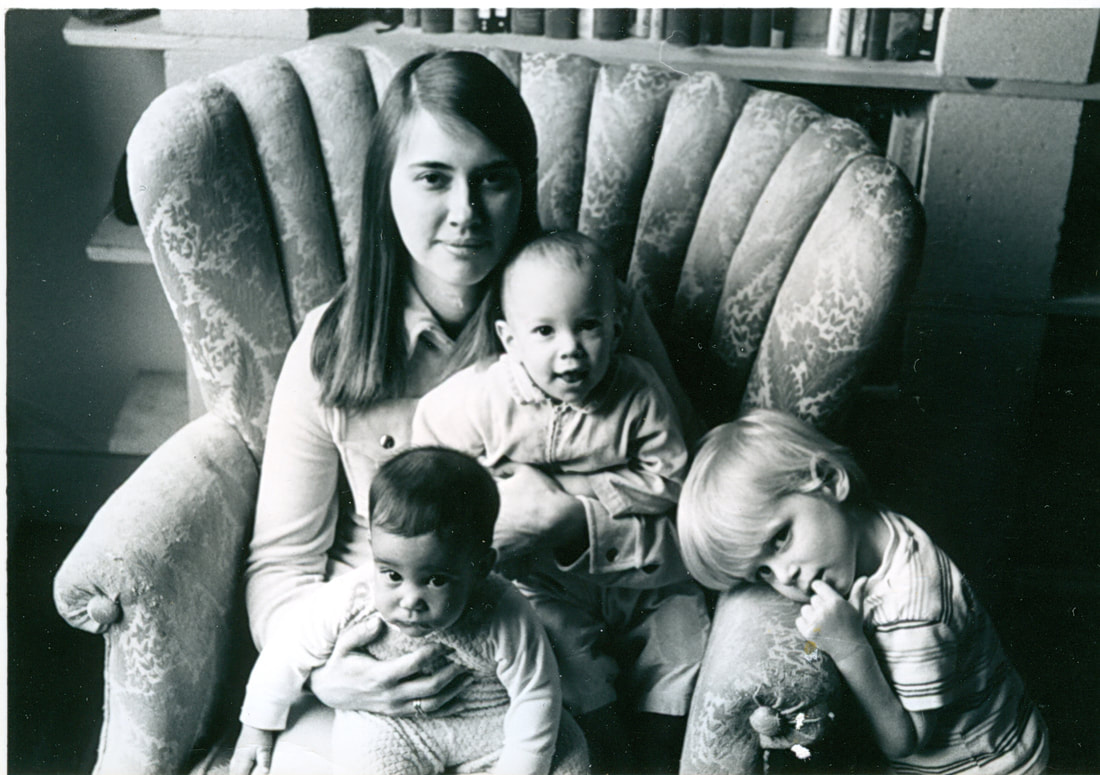

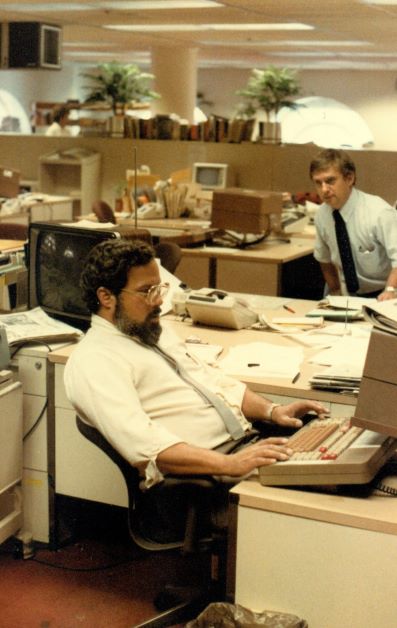

80! I made it. And you can, too. With lots of help and a little luck. IF YOU ARE READING THIS, it means I’ve crossed the finish line. I’ve made it to 80. Can you imagine it? Eighty years old. I never expected that. But in the past few days, as it started looking like it was going to happen, I put together some “Thoughts.” The plan was that at 12:01 a.m., Eastern Daylight Time, I’d press “send.” I can’t predict whether you’ll be interested in 80-year-old Thoughts. You might be hoping for a whiff of “wisdom,” because that’s what tradition says old people are good for. Science suggests otherwise. Here’s something from a recent Washington Post, headlined: TYPE 2 DIABETES MAY ACCELERATE BRAIN FUNCTION DECLINE Relying on brain scans, brain functioning tests and other data from 20,314 people, ages 50 to 80, the researchers compared neurological changes in those who did and did not have Type 2 diabetes. And the important part: In both groups, they found declines in executive functions such as working memory, learning and flexible thinking, as well as declines in brain processing speed. Meaning that “old” people, and I’d argue that 50 hardly counts, are forgetting more, learning less, closed to new ideas and that they are slowpokes. And it’s worse if you have Type 2 diabetes. I’m a Type 2 diabetic. Wisdom suggests that you stop reading here. OKAY, IGNORING an old man’s warnings, let’s get down to basics: Question: “What’s the secret of a long life?” Answer: “That’s a good question.” My wife despises that phrase. She says it’s used by “experts,” who don’t have a clue as to what they're talking about and hoping they can run out the interview clock. However, I do have something to say about the secrets of a long life. Let's start with my parents. They smoked themselves to death and didn’t make it out of their 60s. It wasn’t their fault. When they got addicted to nicotine during the previous century, the only people who knew that cigarette companies were manufacturing death were people at the companies that were making cigarettes. This was massively unfair. My mother and father were gold standard parents: kind, loving, attentive, principled, smart, scorchingly honest and vintage New Deal liberals. Raised in Queens, N.Y., they figured – correctly – that Vermont would be an excellent place to raise kids. My mom quit smoking for two years – her final years as she fought lung cancer so she could celebrate their 40th wedding anniversary. As his beloved Jessie was dying in the next room, my father, the Rev. Harry H. Jones, an Episcopal priest, was in the bathroom, sneaking cigarettes. Mom was 62 when she died. My father died two years later at 65 of a broken heart, which already was compromised by the chemical “products” of fired-up tobacco. My parents got zero help from the Lord. And rescue came too late from the anti-smoking crowd, who included the U.S. Surgeon General and Rhode Island lawyers, who drove the treacherous Joe Camel cartoon from the schoolyards and off the TV screens. QUITTING SMOKING is the secret to a long life? No. No. And no. This is the problem with young people today, they don’t LISTEN! Maybe I should tell you a little about my life. My parents didn’t beat me or my sister. They didn’t lecture us. Didn’t withhold dessert for poor grades. The Reverend Mr. Jones, rector of St. Stephen’s Church in Middlebury, didn’t impose character-building chores like milking the cows every morning. Not that we had any cows, but we did grow up in a postcard, which had a town green and the Green Mountains as a backdrop. My mom read the New York Times cover to cover and subscribed to the New Yorker magazine, which took a bite out of their church-mouse budget. My dad was the first in his family to go to college, and they sent me to college and paid for that. SO, GOOD PARENTS equal a long life? Young people shouldn't jump to conclusions. For one thing, they underestimate luck; nothing happens without it. I was born White and male. My parents moved to Vermont. That’s the luck part. Still, luck isn’t everything. The rest is what people do, the ones who change the world and help to make long lives possible. Do you remember that I mentioned that I went to Muhlenberg College? No? Young people should pay attention. That was where a charismatic professor, who, in between her mental breakdowns, taught me how to write. In an another of my English classes, there was an especially gifted student, who was annoyed with an opinionated, talkative classmate, one who really did talk too much in class, and couldn't stop sharing his opinions. One evening, I bicycled to her place and demanded an answer to a question plaguing me since, as seniors, we’d become friends. Were we, or were we not, going to get married? She said we were. Nobody at the campus could figure that one out. The gorgeous Judy Decking. So smart. So nice. So organized. So funny. So idealistic. So friendly. Cats always purred; babies smiled; everyone said hello. How could something like that happen? MY PLAN AFTER college was to move to Vermont, write Pulitzer-Prize-winning novels. Later, I'd run for the U.S. Senate, since in Vermont, you could befriend everyone, and to be rid of you, they’d send you to Washington. Meanwhile, I would offer my extraordinary talents to newspapers, which, crudely written as they were, would pay the bills. (The young are so gullible.) An editor for United Press International called my dormitory pay phone, wanting to know if I planned to sit on my ass at a second-rate newspaper or work for a real, gods' honest worldwide news operation. The epicenter of this worldwide news operation turned out to be a third-floor walk up in Hartford, CT. (In my first story, I misspelled Connecticut.) Mostly, I sat on my ass, until a veteran UPI'er, before going to lunch and drinking himself into a three-day blackout, sat me down for a lesson on the facts of news-writing. Figure out the most important thing in any story, he said, and make that the first paragraph. Keep it to 30 words or less; less is always better. Next, figure out the second most important thing, and make that the second paragraph, 30 words max. “What about the third paragraph?” I asked, which is when he went to lunch. This was a bombshell, more than I’d learned four years of college. Everything, anything - a bank robbery, the theory of super-cool conductivity or a rabid squirrel in someone’s backyard - could be reduced to 30 words, preferably less. Finally, the world made sense. Next stop, after UPI suggested I relocate to Arizona, was the Springfield Union in nearby Massachusetts. A city editor often called in the middle of the night to check this or that fact and to teach me who’s boss. Next stop, the Providence Journal, which was in Rhode Island, which turned out to be one of the New England states, but easier to spell than Connecticut. Big change. My pay doubled. Why? A few years before I arrived, reporters at the Journal risked their jobs to start a labor union. Life would never be the same for them or for newcomers like me. A living wage, health benefits, a retirement plan, job security (editors wouldn't bully you in the middle of the night). Editors liked me; they taught me more about writing, so that every story didn’t sound like it was written at UPI. I know reporters have a bad reputation and always will. I don’t understand why. My colleagues were smarter, faster, more idealistic than I’d ever be, and what’s more, they were fun to be around. Another point: I loved everything about journalism, especially that magic moment when you discover that one critical thing that makes a real story, so that you'll be the first to tell that to the world, at least the microdot part of the world known as Rhode Island. All the while, the competent, the resourceful and stunning Judy Jones looked after the kids. THE RIGHT JOB, for the right person, with the right wife, leads to a long life, right? Did I say that? No, I didn’t say that. Where do the young people get such ideas? For one thing, reporting was not the “right” job for me. I was, and remain, supremely unqualified for the work. I am astonishingly shy in a field that demands talking to strangers; I’m a terrible note-taker, in a job whose fundamental function is to record exactly what strangers tell you; I have a flawed memory, unsuited for a profession that writes history’s “first draft.” Worse, I’m dyslexic. Which means I get things wrong. If you tell me your phone number, I’ll mix up the figures; give me your name, I’ll rearrange the first and last parts. But people were kind and more. They gave me time to catch up and adapt. Time to write that first paragraph over and over and over until it told you everything in 30 words, preferably less. Time to learn an easy form of shorthand and to transcribe recordings. Time to figure out a system to fact-check dyslexic errors. People always helped, at UPI, at the Springfield Union and especially at the Providence Journal. Those colleagues – did I mention them already? They were so smart, so fast, so eloquent, willing to read my story drafts, to tell me how they did their work, to tip me to story ideas. Just watching them was a privilege and an education. Many of those role models are dead. Which is another thing about people who last for a long time. They live with ghosts, who are real, and who are a comfort. THERE’S MORE? When a life is long, it takes more than a Tweet or 30 words to explain. Young people should realize that. A few months after Judy and I were married in 1964, I was drafted. The Vietnam War – you’ve heard of it? A doctor at our college, who was not a fan of the war, mailed x-rays of my right knee that had been mashed up during freshman soccer practice. When I reported for “duty,” I handed over the x-rays, as required by the Army. So, other people went to Vietnam and didn’t return, or if they did, weren’t the same. I’m troubled by that. But it’s a fact, and another reason why, at midnight, I made it to 80. In 2008, I was diagnosed with prostate cancer, Type 2 diabetes, and a 90 percent blocked artery. A bit of radiation, some pills and a stent, and I was back on the road to 80. One evening, I was driving a small and old (of course) car. Traffic was light, as it's phrased in the police reports; the weather was clear; Driver #1 was traveling at the speed limit; Driver #2, in a pickup and texting on his “smart” phone, "made contact" with the rear of the sedan of Driver #1, sending it flying onto the breakdown lane. The engine was still purring as I got out. The entire rear end of the car was in the back seat. Which was exactly where engineers wanted it to be, having designed a crumple zone to absorb a direct hit. We have three adult children. You’d like them. One lives 3 miles away; another 20; and the third, 78. Most families need frequent flier miles to get together. Our children don’t seem to mind a brief trip, or spending time with old people, who tell the same stories. Our granddaughter has a baby, which both makes us great grandparents, and grateful for having lived long enough to hold her. FINALLY, the secret.

I got to be 80 because of what other people did. My mother and father were parents that other people wished were theirs. News people I never met risked their jobs to make a great newspaper a place were a reporter with shortcomings could do democracy’s work for more than three decades. Crusaders near and far battled tobacco companies; automotive engineers, with a nudge from Ralph Nader, designed crumple zones. A doctor mailed x-rays to the Army. My bosses were mentors. Shrinks diagnosed dyslexia. FDR presided over the New Deal. LBJ got the voting rights bill done and dreamed of a Great Society. A mad professor taught me about writing, and an alcoholic took up my cause at UPI. Doctors found all the scary ailments and acted in time. In 1964, Judy Decking said yes, took care of the children, and had a long career in government and the non-profit world; she's headed for the 80 line in November. We’ve become used to thinking, during the Trump years and the after-Trump years, which have been just as bad, that the world is packed solid with mean, evil, destructive people. They’re everywhere: moving to the Sunbelt, invading Ukraine, swarming the Capitol, plotting to rig the next election, spreading lies. So, it’s easy to forget there’s a bunch of other people, who are determined to make things better. These are people who change the world, and they never stop. We owe them our lives.

5 Comments

Karen Daviw

6/10/2022 07:24:52 am

Outstanding! Happy Birthday.

Reply

Janet Cusick

6/10/2022 10:24:07 am

Happy Birthday Brian! We're glad you made it!

Reply

Karen Lee Ziner

6/10/2022 01:45:34 pm

HAPPY 80TH BIRTHDAY, BRIAN!!! A great milestone; hope there is cake involved. Best, Karen

Reply

Jody M McPhillips

6/26/2022 05:26:12 pm

great piece, Bri! Makes me want to keep trucking. Once again, you're my role model❤️

Reply

Jean Johnson

6/27/2022 09:00:04 am

Happy Birthday Brian! We’ve moved to idyllic Vermont , part time, hoping for peace of mind and heart. It’s working. And knowing you are on the planet and continuing to inspire, works too. You help make a good and thoughtful life for me. Thank you. Stay well. Hi to Judy.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

BRIAN C. JONES

I'VE BEEN a reporter and writer for 60 years, long enough to have learned that journalists don't know very much, although I've met some smart ones.

Mainly, what reporters know comes from asking other people questions and fretting about their answers. This blog is a successor to one inspired by our dog, Phoebe, who was smart, sweet and the antithesis of Donald Trump. She died Feb. 3, 2022, and I don't see getting over that very soon. Occasionally, I think about trying to reach her via cell phone. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed